Celebrating Four Years of the James Webb Space Telescope

Written by Alex Fisher

Thumbnail & Banner Photo by NASA/Chris Gunn, used with permission from NASA.

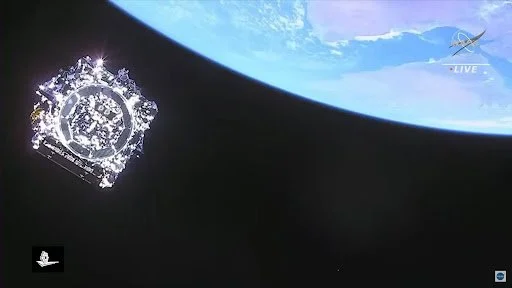

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launched into space on December 25th, 2021. I can vividly recall waking up at 4:00 AM (11:00 AM UTC) that morning, hours before anyone else in my household, turning on the NASA livestream and getting cozy on the couch with a hot chocolate as the technicians did the final checks on the Ariane 5 rocket carrying the JWST. Nearly an hour and a half later, at 5:20 AM (12:20 PM UTC), the rocket lifted off, and the JWST began its long journey towards the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrangian point, four times further away from the Earth than the Moon is at its most distant.

The successful launch of the JWST served as the culmination of decades of work by countless scientists and engineers, who had all worked together to create one of the greatest scientific instruments in human history. I had the incredible fortune of sitting down with and interviewing Dr. Marcin Sawicki, Professor of Astronomy and Physics at Saint Mary’s University and author of the book Webb’s Cosmos: Images and Discoveries from the James Webb Space Telescope. Dr. Sawicki was one of the many people to contribute to the JWST’s development, having helped develop one of its scientific instruments.

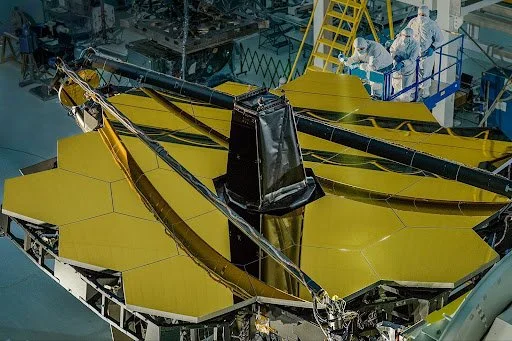

JWST Artist Conception by NASA GSFC/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez, used with permission from NASA.

The story of the JWST begins in 1989, prior to the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope in 1990. More than 130 astronomers and engineers were brought together for the Next Generation Space Telescope Workshop to begin the discussion of Hubble’s successor, then known as the Next Generation Space Telescope (NGST). The proposed goal was to build a much larger telescope than Hubble that could observe infrared (IR) light, rather than the visible light spectrum. This would allow the telescope to observe objects hidden behind the dust and gas in the universe, allowing it to see much further and with much more detail than any telescope that came before it. Additionally, given that light takes time to travel (the speed of light is just shy of 300,000,000 meters per second), the NGST would be able to look further back in time than any telescope that came before, allowing us to look at the very early universe. As Dr. Sawicki describes it: “Telescopes are like time machines. The more distant the object, the longer it takes the light to reach us. You’re seeing objects as they were millions or billions of years ago, and Webb allows us to go farther than ever before.”

Things moved slowly over the next decade, but in 1999, NASA contracted several companies to estimate the costs and come up with an early design for the project. In 2002, the NGST was renamed in honour of James E. Webb, administrator of NASA between February of 1961 and October of 1968. Construction of the JWST fully commenced in 2004.

Over the following 17 years, as the design of the JWST was refined, tested, and eventually completed, a total of four instruments were chosen to be mounted on the telescope. The most notable of these is the FGS/NIRISS instrument, which was designed and built in Canada.

FGS/NIRISS is essentially two separate instruments bundled together, both objects having been made by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). The Fine Guidance Sensor, or FGS, works by pinpointing bright known stars and using them to angle the telescope and ensure that it is aimed in the right direction. The Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, or NIRISS, is the scientific instrument that Dr. Sawicki contributed to. It functions as both a camera and a spectrograph, breaking up a beam of light into its constituent wavelengths to learn more about a given astronomical object. Unlike other instruments on the JWST, NIRISS can perform this analysis for all of the objects within its field of view at any given time, making it an extremely powerful and efficient instrument. When I asked about his contributions to the project, Dr. Sawicki clarified that he was responsible for helping guide the requirements and specifications of the instrument, based on the scientific goals of the JWST. He also added that he was actually the person who came up with the name for the NIRISS instrument!

Webb's First Deep Field by NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI, used with permission from NASA. Note the characteristic six-pointed glare around the brightest objects, caused by the JWST’s hexagonal mirror structure.

The first image from the JWST was released in early July of 2022, six and a half months after its successful launch. This image, seen above, is titled Webb’s First Deep Field, and it contains thousands of galaxies similar to our own Milky Way Galaxy. All is imaged within “a patch of sky approximately the size of a grain of sand held at arm's length by someone on the ground.” It was immediately compared to the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, a similar image of the same patch of sky taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2004. In less than a tenth of the exposure time compared to Hubble, the JWST captured even more detail, including more and older galaxies, compared to its predecessor.

While the JWST has produced many astonishingly beautiful pictures of space and astronomical objects, its main goal has always been scientific advancement. Dr. Sawicki and his research group, for example, are interested in understanding how galaxies like our own Milky Way first formed and how they have evolved over time. While galaxies take billions of years to evolve, far longer than any human timescale, Dr. Sawicki explained that galaxy evolution can be understood by looking at galaxies of varying ages to model how they change with time. He is also involved with the Canadian NIRISS Unbiased Cluster Survey (CANUCS) project, which looks at massive galaxy clusters. These clusters can actually bend the path of light coming from objects behind them in a process known as gravitational lensing, creating distorted projections of distant galaxies. Far from being a negative effect, these ‘lensing clusters’ can amplify the light from these most distant galaxies, allowing us to see them in far more detail than would otherwise be possible.

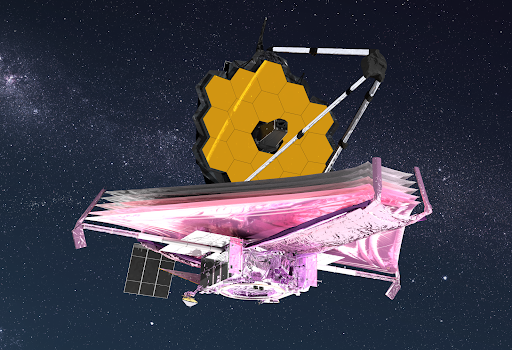

Question Mark Galaxy - Hubble and Webb by NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Vicente Estrada-Carpenter (Saint Mary's University), used with permission from NASA.

One example of gravitational lensing enhancing our view of a distant galaxy can be seen in the image above in the Cosmic Question Mark, made up of an interacting pair of galaxies. The interacting galaxies, which are thought to show a snapshot of a process our own galaxy may once have undergone, do not actually form a question mark shape in space. Rather, a galaxy cluster positioned between us and the galaxy pair has distorted their image and even caused multiple projections of the same galaxies, turning them into the shape of a question mark by pure happenstance.

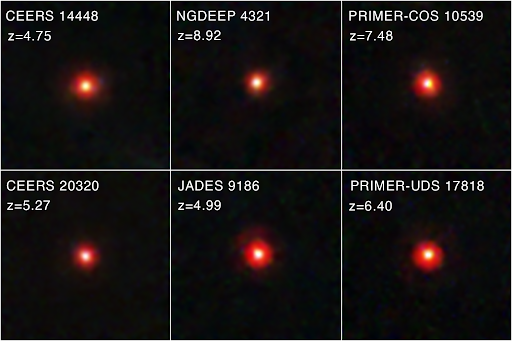

Dr. Sawicki is hardly the only person to have worked with data from the JWST. More than a terabyte of data from the JWST is already publicly available, and the telescope has already led to profound advancements in our understanding of the universe. When I asked Dr. Sawicki about how JWST data has impacted astrophysics in general, he told me that one of the most surprising discoveries was that there were already huge galaxies present in the very early universe, challenging previous observations and current theoretical models. Additionally, the JWST has led to the discovery of several new types of astronomical objects, most notably “little red dots.” These objects, which exist only in the early universe, are currently thought to be young supermassive black holes.

Image by NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Dale Kocevski (Colby College), used with permission from NASA. The z numbers refer to the redshifts of each of the six objects. A higher redshift means that the object is older and more distant.

The JWST has also revolutionized the search for and analysis of exoplanets—planets located beyond our own solar system—says Dr. Sawicki. By observing exoplanet transits, when an exoplanet passes in front of its host star and the star’s light temporarily dims, the JWST’s extremely sensitive instruments allow it to learn much about an exoplanet’s composition and atmosphere.

All of these incredible new discoveries and the amazing capabilities of the JWST have led to it being incredibly popular with astronomers, according to Dr. Sawicki. He explained that the telescope receives thirteen times more requests than it has actual observation time, making it more oversubscribed than any other telescope currently in use.

We’re already four years into the JWST’s minimum mission goal of five years, and the science it has already put out has been incredible for furthering our understanding of the universe. Additionally, due to the incredible precision of the Ariane 5 rocket that took the JWST into space, the mission’s expected lifetime was able to be doubled to a full twenty years. This means we’re now only a fifth of the way into the JWST’s expected operational lifetime. Who can predict what incredible discoveries the telescope will lead to next?

Humanity’s Last Glimpse of the James Webb Space Telescope by Arianespace, ESA, NASA, CSA, CNES, used with permission from NASA.

The final question I asked Dr. Sawicki was if there was anything about the JWST or astronomy in general that he would like to communicate to the SMU Journal’s readers. He said that he wanted our readers to be aware that the JWST does not only belong to astronomers: it belongs to everyone in some small way. Astronomers and astronomy students may get to study the data from the JWST, but much of this data—not to mention countless beautiful pictures—is freely available to the public. No matter who you are, astronomy gives you the opportunity to find perspective about your place in the universe and the things that truly matter. All you need to do to enjoy it is to browse through some of the many images available online or simply look up into the night sky. As Dr. Sawicki puts it: “Nature paints beautiful pictures in the sky, and we can all enjoy them.”

Do you have any questions about the JWST? Are you interested in more articles about astronomy and physics? Let us know on our social media pages.